The Seeds of Change 1600 - 1929

What would you like to find?

Downloadable Media: The Seeds of Change

Imagery

Video

Panama Canal

Audio

Imagine you are on a journey to America, leaving behind everything you have known for untold dangers ahead. You are willing to take the risk because you want to start a new life where you will be free to work hard on your own land. The New World means a new life - a life of possiblities.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, in America, historic events are shaping an exciting way of life for common citizens of the United States. Vast, rich lands set the stage for people to make their dreams a reality. Their hard work earns them cash, free time, and a life beyond basic needs. Their system of government is the foundation for this prosperity; established through the good fortune of free, plentiful land and a century long experiment in democracy.

How did the practices of this new kind of government support a revolution in agricultural science, technology, and education? How did agriculture help the United States of America become a prosperous, thriving nation and major world power? Consider the answers to these questions as you enjoy "Growing a Nation: the Story of American Agriculture".

The first permanent English settlement was established at Jamestown, Virginia.

Jamestown Saved by Tobacco

Arriving on three ships, The Susan Constant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery, 104 men and boys arrived from England and named the settlement after their king, James I. The area was chosen because it was far enough inland and surrounded by water on three sides, which made it easily defensible against Spanish invaders, and was not currently inhabited by native Americans. A triangular fort was constructed by June 15 to protect the settlers from the local Powhatan Tribe, whose hunting grounds were located on the settlement area.

While the relationship between the settlers and the natives was tenuous, the Powhatans sent food to Jamestown Settlement when disease from drinking salt water and drought conditions devastated the population. During the winter of 1609-1610, known as the Starving Time, 80-90% of the settlers had perished due to disease and starvation. Help arrived in May 1610 with the arrival of Sir Thomas Gates, the new governor. Sir John Rolfe brought tobacco seeds with him to the colony in 1612, which turned the settlement into a profitable endeavor for the Virginia Company.

The Growth of the Tobacco Trade

Questions

Based on "The Growth of the Tobacco Trade":

What types of economic ventures did Jamestown settlers attempt? Why did they try these experiments?

Compare and contrast the views of Thomas Hariot and James I on the nature of tobacco.

What were the benefits and consequences of growing tobacco in the colony?

Stebbins, Sarah. "A Short History of Jamestown." National Park Service. 2011. Web. 27 July 2018.

Agriculture in Jamestown

All forms of domestic livestock, except turkeys, were imported at some time. Crops from the New World were adapted to English diets and lifestyles, and included maize, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkins, gourds, squashes, watermelons, beans, grapes, berries, pecans, black walnuts, peanuts, maple sugar, tobacco, and cotton.

In 1609, settlers mined bog iron ore near Jamestown, and by 1619, the first iron production facility in North America, Falling Creek Ironworks, was established along the James River. However, due to native attacks in 1622, the facility did not last long.

Take the link to view an artifact found at the Historic Jamestowne archaeological site:

Questions

What was the emphasis at Jamestown during its first few years, rather than cultivating food?

Is there a relationship between the crops grown and the Falling Creek Ironworks? Explain. How might this relate to farming today?

"Agricultural Fields." Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, Inc. 2011. Web 31 July 2018.

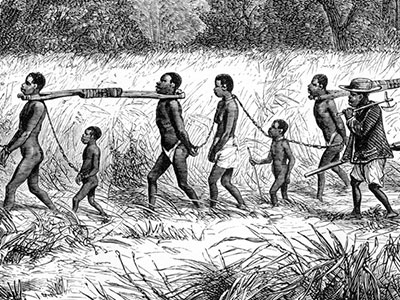

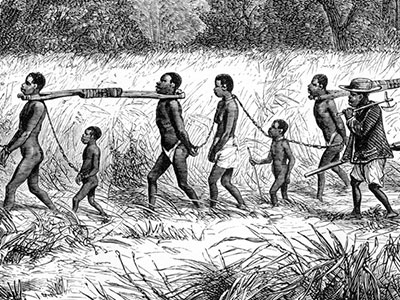

In 1619, the first African slaves were brought to Virginia from Angola in West Central Africa; by 1700, slaves were displacing southern indentured servants. For additional information about indentured servants in Colonial Virginia, and the transition to slavery use the links below.

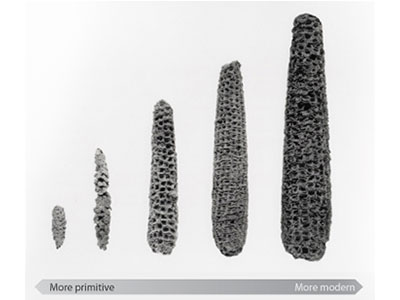

Three Sisters Gardening

Corn, beans, and squash were some of the staple foods of Native American cultures. These crops were known as the "three sisters" because they were commonly planted together as companion crops: each benefits the others as they grow. Utilize the resource below to learn more about who the "three sisters" are, their importance, and when and how to plant them.

Questions

How did these plants benefit each other?

What principles could farmers and scientists learn from this agricultural technique that could be used in growing other crops?

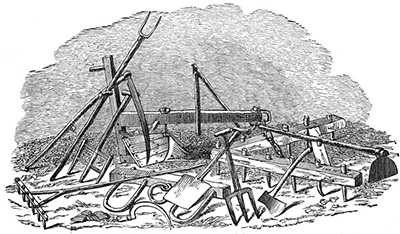

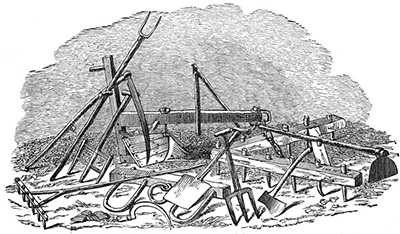

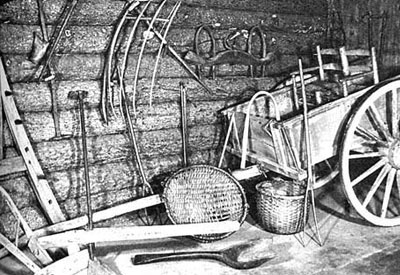

Early Farm Implements

Questions

Looking at this equipment, what agricultural products would you guess this farmer raised?

Do you think these tools belonged to a poor farmer or a wealthy farmer? Why?

In what ways, if any, would these tools be labor-saving devices?

How do you think this farmer obtained these tools?

Native American Agriculture

Contrary to what many people believe today, the land the first Europeans saw in America did not consist entirely of untouched land and pristine forests. Read this excerpted account of the history of agriculture in southeastern America before the arrival of Europeans.

For a minimum of 12,000 years, Native Americans (or Indians as was the European term for Native Americans) had been skillfully manipulating the environment, primarily with fire. The landscapes that the first Europeans encountered were not undisturbed, dense forests as many people today envision. Knowledgeable humans skillfully modified the landscapes to support a population numbering in the millions.

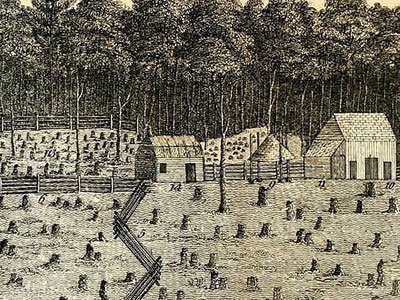

The cultivation of the tropical maize, flint corn, and beans along the Mississippi River and in the Gulf States marks the beginning of the Mississippian culture.... The adopted intensive agricultural practices from Mesoamerica influenced the landscape in the Southeast dramatically. Large native populations developed in much of the lower South because the more sophisticated agricultural system produced more food. Without draft animals or plows, agriculture with stone or wood implements was limited to the tillable soils of floodplains, where spring flooding helped renew soil fertility. Agricultural fields were cleared first by girdling trees and then burning the area. The ashes acted as fertilizer. Stumps were also removed over time and in the spring old agricultural debris was burned off before planting. When soil fertility declined from cultivation, fields lay fallow but were burned annually to maintain their open condition for future agricultural use. Most of the cultivatable floodplains of the Southeast were cleared of forest and managed in this way.

During the period of European contact, disease-related mortality rose to levels previously unknown; and the impact of these diseases was swift and harsh. In areas of the Caribbean, entire native populations were erased. These epidemic diseases were transported from the Caribbean to Mexico and Central America and may have preceded the arrival of the Spanish in these areas. Epidemic diseases were introduced to the natives of the Southeast at about the same time. During the 100 years of Spanish exploration, disease decimated the dominant Mississippian cultures of the Southeast and resulted in their collapse by 1600.

European diseases not only depopulated Native Americans and their culture (depopulation is estimated as high as 90 to 95 percent), they disrupted the social structure of native societies. As in all epidemics, mortality was disproportionably greater among the young and old. Loss of the younger generation had profound effects on the integrity of American Indian societies. The loss of manpower created difficulties maintaining agricultural systems and fire regimes. Loss of the elderly eliminated a storehouse of knowledge, tradition, and custom.

The arrival of the English continued the epidemic diseases and decimation of American Indians for at least another century. English trade with the natives lured them into dependence on the European fur market for European goods, which in turn diminished the traditional reasons for hunting, while devastating wildlife populations. As the fire regimes and agricultural systems gradually eroded, the appearance of the land began to change. Uncontrolled vegetation began to form an unbroken shroud. The extensive canelands witnessed by English settlers as they pushed inland were signs that the thousands-of-years-old fire ecosystems created by the natives were in decline."

Questions

What were the agriculture practices in the Americas before European settlers arrived?

How and why did Native American agriculture change after Europeans arrived?

Wayne D. Carroll, Peter R. Kapeluck, Richard A. Harper, and David H. Van Lear, "Background Paper: Historical Overview of the Southern Forest Landscape and Associated Resources," Final Report Technical, Southern Forest Resource Assessment [online].

Sheep and Wool

Wool played an important role in colonial America. Before the Revolutionary War, most of the finest textiles and fashionable styles were imported from Great Britain. Many colonists wanted to produce their own clothing and textile goods. Wool and linen were the most common materials used. Homespun clothes, clothes that were produced by the colonists, reduced the amount of clothing that had to be bought from England.

In 1699, under the rule of King William III, the British Parliament issued the Wool Act which prohibited American colonists from exporting wool or wool products outside of the colony in which it was produced. The king banned the export of sheep to the American colonies in an effort to protect England’s wool industry. Wool could only be imported into the colonies by Great Britain. The Wool Act was one of a series of taxes that divided Great Britain and its colonies in America.

The colonists began protesting the Wool Act by refusing to purchase or wear English textiles. Many colonists refused to purchase English goods. It became a patriotic act to wear American homespun clothing. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin are notable figures who wore homespun clothing as a patriotic statement of their devotion to American independence and freedom. In the American colonies, spinning and weaving wool became a necessity and a patriotic duty.

In colonial times, the process of making wool cloth began with shearing sheep in early spring with hand clippers. The wool was cleaned through a process called scouring in which the wool underwent a series of baths before it was laid out to dry.

Wool grease is produced as part of the wool’s growth and helps protect the sheep’s wool and skin from the environment. Scouring removes this grease from the wool. The grease can be captured from the scouring water. When it is refined, this grease is known as lanolin. Lanolin can be used in moisturizers, cosmetics, medicine, and industrial applications.

In preparation for spinning, wool must be carded. The colonists used hand carders to comb the wool, remove debris, and untangle the fibers, aligning them parallel with each other. Colonists used dye formulas that included insects, roots, flowers, nuts, seeds, tree bark, leaves, or berries. Because of the toxic chemistry, many of these colonial dyes have been deemed unsafe in our modern era. The dyeing process involved soaking wool in kettles of dye over fires for several hours.

Wool was spun into thread or yarn by tightly twisting the fibers using a spinning wheel. Weavers turned the wool thread into cloth using looms. Wool was also felted, a process of matting fibers together, to make products such as hats and slippers.

Questions

How much time do you think it would have taken make a felted wool coat or spin yarn for a sweater?

How many articles of clothing might a colonial have?

Lynn Wallin, National Center for Agricultural Literacy

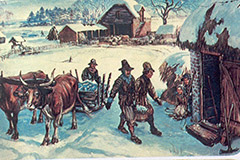

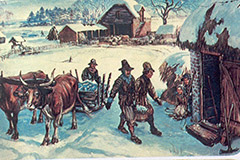

During the early 1700s agricultural technology consisted of the following: oxen and horses for power, crude wooden plows, all sowing by hand, cultivating by hoe, hay and grain cutting with a sickle (one-handed tool with short handle and curved blade), and threshing with a flail (a tool made with two long sticks attached by a strip of leather). As the century came to a close farming technology had advanced from hand tools to farming equipment that used horses and steam power. These innovations along with indentured servant labor (in the north) and African slaves (in the south) increased farm productivity.

Flail

A flail is an agricultural tool that was used for threshing grain, the removal of the husks from the grain. It consisted of two pieces of wood, one longer, the other shorter, and was attached by a piece of rope, leather, or small chain. The grain would be "beaten" or threshed with the flail, which allowed a person to be able to thresh about seven bushes of grain a day. The flail was replaced by the thresher in the mid-19th Century, with the growth of industrialization.

Questions

Why was the flail an ancient Egyptian symbol?

What is the value of using a flail over a different method for removing grain from its husks?

"Flail". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Web. 7 August 2018.

Sickle

The sickle, an agricultural implement that has a curved blade with a short handle, was used as early as the Iron Age, and continues to be one of the most widely used around the globe. While using a sickle to reap grain or cut hay is slow and tedious, it is inexpensive.

Questions

Why was the sickle a part of the symbol from the former Soviet Union?

What advantages does using a sickle have for farmers around the world?

"Sickle". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Web. 7 August 2018.

Jeffersons' Plow

In addition to being a philosopher, statesman, and scientist, Thomas Jefferson was also an inventor, always looking for ways to improve his farm.

Visit the Thomas Jefferson Monticello website to learn about one of his inventions in 1794 the "Mouldboard Plow of Least Resistance."

Questions

Why did Thomas Jefferson design this new plow for his home in Monticello?

Why was Thomas Jefferson successful in so many areas of his life?

Why was he so passionate about agriculture and improving farming?

First Cast-Iron Plow Patent

Charles Newbold, of Burlington County, NJ, patented the first cast-iron plow in 1797. Newbold ran into a couple of issues getting farmers to use his plow, 1) farmers were afraid that the iron would poison the soil and 2) farmers that used the plow complained the metal wore down quickly and was brittle.

Questions

How would the invention of a reliable plow increase farm production?

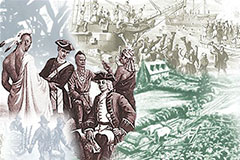

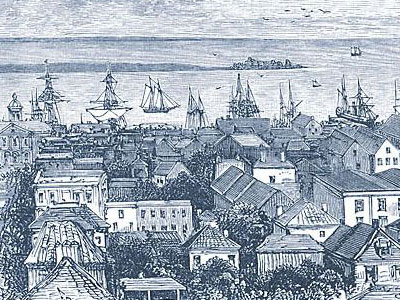

Tobacco was the important money crop, and almost every ship that sailed from a plantation wharf carried hogsheads of the ‘delightful weed’ in its hold. Many other commodities too, were shipped to the mother country as well as to New England, the middle colonies, Barbados, Madeira, Bermuda, and Jamaica.

Colonial Agriculture & Trade

Colonial Williamsburg maintains a website describing life and society during colonial times. Explore their 18th Century Trades Sampler page to learn about trade practices of the time.

Questions

What was one of the most important crops in colonial Virginia?

How much labor did it require to produce this key southern crop for export?

What resources did southern planters have for producing this crop?

If many of the crops grown in the southern part of America required large numbers of workers, how would southern farmers react to changes that affected their labor supply?

Agriculture in Virginia

Read the excerpt below regarding trade and the English colony of Virginia in 1732.

“Tobacco was the important money crop, and almost every ship that sailed from a plantation wharf carried hogsheads of the ‘delightful weed’ in its hold. Many other commodities too, were shipped to the mother country as well as to New England, the middle colonies, Barbados, Madeira, Bermuda, and Jamaica. Exports from one Virginia shipping district -- Porth South Potomac -- in 1732 included (besides tobacco) staves, timber, corn, wheat, peas, beans, masts, pig iron, feathers, pork, cotton, earthernware ‘parcels,’ woodenware ‘parcels,’ bacon, hides, deerskins, beaver skins, oak and walnut logs, cider and cider casks, beef, wine pipes, snakeroot, tallow, pewter and brass ‘parcels,’ and copper ore casks. Items imported included rum, salt, Irish linen, fish, chocolate, molasses, sugar, earthernware, ‘woodware,’ millstones, Madeira wine, cheese, rice, ironware, and ‘parcels from Great Britain.’ The latter ‘parcels’ included furniture fabrics, rugs, pottery and porcelain, silver, pewter, copper and brassware, and other household furnishings and accessories needed by the colonists.”

Questions

What agricultural products did the people of Virginia export?

Which agricultural products might they have had to import, and why?

From the text excerpt, what can you determine about the importance of trade between the American colonies and England?

Tobacco Trade

While tobacco was the most significant cash crop in Virginia, like all agricultural products, it was dependent upon favorable weather conditions. In order to grow tobacco successfully, farmers needed a warm climate with rich, well-drained soil. In addition, tobacco tended to deplete the soil of its nutrients after three of four years of cultivation, so the need for crop rotation was essential.

According to historian Tony Williams, "The soil exhaustion that resulted from raising tobacco caused planters such as George Washington to diversify their plantations and switch production into growing grains. The port of Norfolk thus became a major exporter in the wheat and corn." (2009, p. 30)

Hurricane of Independence, by Williams, tells about a gentleman named Landon Carter who experimented with various crops. He took meteorological data on a daily basis in attempt to "master nature." However, he proved to be rather unsuccessful as he watched his crops die from early frosts, too much, or too little rain. Carter "confided to his diary that he had less control than he desired and that, 'The farmer is nothing without weather.' Weather was a matter of chance, and he was its pawn. The farmer had little choice but to 'always feel the weather and rejoice when it is good and be patient when it is unseasonable.'" (2009, p. 63)

Weather is certainly beyond human control, but there was more to raising tobacco than issues with the weather. Tony Williams explains, "Simply growing the crop was an extremely difficult task and one that often vexed the planters.

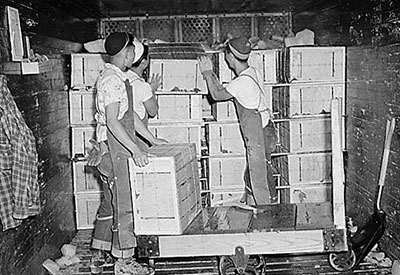

"The 'noxious, stinking weed,' as King James I called it, was unlike most other crops in that it demanded year-round labor and careful attention. After the twelve days of Christmas and the holiday from work for the slaves was over, the intensive planting began as tobacco seeds were sown with animal or ash manure and covered with branches to protect against frost. Because of the vulnerability of the plants, ten plants were planted for every one eventually cut.

In late spring, running slaves carried the seedlings to their fields and planted them during wet weather to avoid damaging their roots. Slaves worked all summer to weed the fields and fight against pests. The slaves then 'topped' the tobacco in order to prevent flowering, which would draw nutrients away from valuable leaves.

In September, during hurricane season, the slaves would cut the plants according to the planters' judgment. This was a critical decision because if the leaves were too moist, they would rot on the ships crossing the Atlantic. Conversely, cutting them when they were dry meant that they would become brittle and disintegrate.

The 'harvest' did not mean the end of the work for the slaves because the tobacco had to be cured in special curing barns to dry. If the weather were too rainy, special fires would be lit to prevent rot--hopefully without burning down the curing barn. Slaves then stripped the leaves from the stalks and hung them to dry before they were pressed and loaded into thousand-pound hogshead barrels for the trip to England or Scotland. The process generally was not completed before the next year's crop was laid." (Williams, 2009, p. 66)

Successful tobacco crops meant lucrative profits for planters, which promoted a boost for the global economy. Tobacco plantation owners now had the means to purchase goods from Europe.

Williams continues, "Planters were voracious consumers of luxury goods from Great Britain as they sought to emulate the lifestyles of fashionable Europeans. Great amounts of goods were conspicuously consumed to adorn their great houses. George Washington, for example, put in an order for sterling silver forks with ivory handles, pewter plates engraved with his crest, a carriage, and a fashionable summer cloak and hat for his wife Martha." (2009, p. 67)

Questions

Based on the excerpt from Tony Williams' book, Hurricane of Independence, why did tobacco planters need to diversify their plantations?

Who was Landon Carter, and what was his attitude about weather and farming?

Describe the process of the cultivation and harvest of tobacco.

What was the effect of successful tobacco crops on the world economy in the 1700s?

Williams, Tony. Hurricane of Independence. Naperville: Sourcebooks, Inc., 2009. Print.

The first European settlers in America quickly learned that they had to adapt or starve. During the winter of 1609 to 1610, two-thirds of the settlers in Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in America, died. Native Americans taught the survivors how to grow corn, pumpkin and squash. Corn and beans were planted together in small mounds so the bean vines could grow up along the cornstalks. The beans also added nitrogen to the soil. Pumpkins and other kinds of squash were planted between the mounds. Seeds were saved for the next year's crop. Another Native-grown plant, tobacco, became the primary cash crop of colonial America. Eventually, through trial and error, the settlers were also able to adapt European crops to the New World.

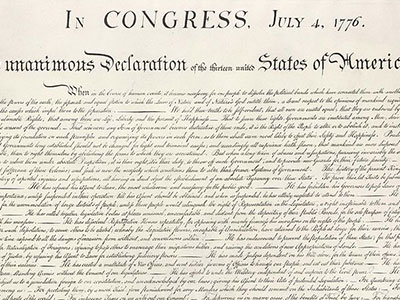

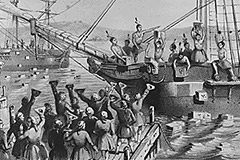

As the English gained control of America, their merchants sought new markets for colony crops. However, the British government imposed heavy duties on many agricultural products from the colonies and limited the export of more valuable products like tobacco, indigo, wheat and livestock. These restrictions created resentment among the Colonists and were a major cause of the American Revolution.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, England adopted a series of laws known as “Parliamentary Acts.” These laws regulated trade from the American colonies by requiring that goods exported to England be sent on British ships.

Parliamentary Acts

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, England adopted a series of laws known as “Parliamentary Acts.” These laws regulated trade from the American colonies by requiring that goods exported to England be sent on British ships. One section of these laws, the Navigation Acts, required that the colonies transport their most expensive products back to England and pay costly import taxes for this right. The Navigation Acts also restricted other exports from the colonies. Although these laws had been in effect for many years, they were not strictly enforced. Beginning in 1764, however, the British passed additional acts that heavily taxed the colonies and eventually led to open rebellion.

Questions

How might these various acts affect agricultural trade?

What did the colonists mean when they claimed they had “taxation without representation”?

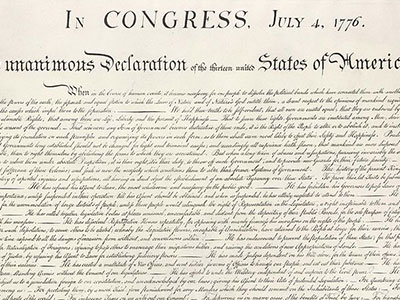

The Declaration of Independence resulted partly from British controls on farm exports, restrictions on land titles, and limitations on western settlement.

According to scholar Staughton Lynd and Temple University historian David Waldstreicher, the seeds of the American Revolution were sown by economic issues: "From the mid-18th century right up to the signing of the Declaration, Americans objected to a myriad of British imperial policies principally on economic grounds. The antitax sentiment of the Boston Tea Party in 1773 is well known, but Americans also protested British attempts to requisition resources during the Seven Years War (175663), imperial currency manipulation that left the colonies strapped, and prohibitions on trade with the French West Indies, along with many other policies."

Lynd, Staughton and Waldstreicher, David. "Free Trade, Sovereignty, and Slavery: Toward an Economic Interpretation of American Independence." William and Mary Quarterly. October 2011. Web. 27 July 2018.

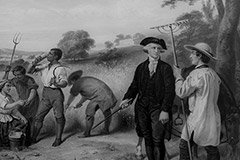

Many of the leaders of the American Revolution, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, were farmers. Both Washington and Jefferson were interested in experimenting with agriculture. At this Mount Vernon, Virginia farm, George Washington experimented with crop rotation and with new seeds and plants. He also became the Nation's first mule breeder, using animals given to him by the king of Spain.

Thomas Jefferson also enjoyed experimenting with agriculture on his Virginia estate at Monticello. Both Washington and Jefferson helped organize societies for improving agriculture. These societies were pioneers in agricultural science and education. Some societies issued reports, published journals, and sponsored agricultural fairs to encourage agricultural improvement.

Early Americans were self-sufficient; ninety-three percent of them were farmers, and free land, rich soil, and a temperate climate helped them do well. Farmers began to use horsepower to pull newly invented farm implements like the broadcast seeder and the mechanized grain reaper. These implements improved working conditions for farmers and provided more cash so that they could enjoy a better standard of living. Immigrants came to America in droves, exchanging their own indentured labor for passage to seemingly limitless American freedom, land, and opportunity.

In March 1765, British Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the first direct tax on the American colonies, which included taxation on printed documents, newspapers, dice, and playing cards.

In July 1765, the Sons of Liberty organized their underground operation to boycott British goods in protest of the Stamp Act.

In October 1765, the Stamp Act Congress convened in New York City to prepare a resolution to King George III and Parliament, asking for the repeal of the Stamp Act and the Acts of 1764.

In December 1765, over 200 Boston merchants joined in boycotting British imported goods, which helped further the boycott movement.

Shay's Rebellion, a farmers' revolt against high taxes and deflation in western Massachusetts, demonstrated the general resentment from the economic crisis that followed the American Revolution.

In 1791, the First National Bank was chartered and signed by George Washington. Its purpose was to manage the massive Revolutionary War debt and create a standard currency for the nation.

In 1790, the total U.S. population was 3,929,214; farmers made up 90% of the labor force.

On July 31, 1790 Samuel Hopkins was issued the first patent for a process of making potash, an ingredient used in fertilizer. The patent was signed by President George Washington. Hopkins was born in Vermont, but was living in Philadelphia, Pa. when the patent was granted. Potash, or potassium, is the third major plant and crop nutrient after nitrogen and phosphorus. It has been used since antiquity as a soil fertilizer (about 90% of current use). Consider how the easy availability of this element would impact agriculture production.

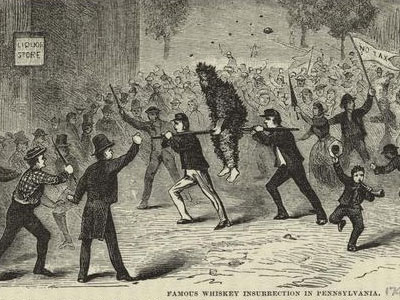

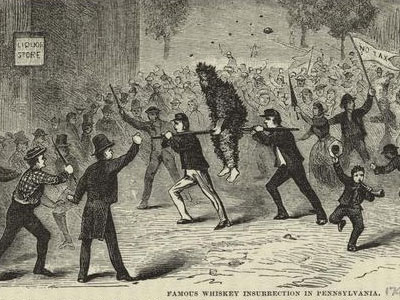

The Whiskey Rebellion, a farmers' revolt against taxes on grain in whiskey, began in 1791 when the federal government authorized its first tax on a domestic product in order to reduce the national debt. In 1794, opposition among farmers and distillers in western Pennsylvania grew to the point where George Washington dispatched troops to quell the rebellion.

By the 1800s the Northern states began to industrialize and export manufactured goods. As the Northern states industrialized they attracted new immigrants while the South’s population stagnated. In 1800 half of all Americans lived in the South, but by 1850 only one-third of the population was there.

The Southern economy relied on producing and exporting cotton, sugar, rice, tobacco and wheat. The South also depended heavily on food imported from the upper-Mississippi valley. Production of work intensive cash crops like cotton and tobacco expanded and the Southern economy became increasingly dependent on slave labor to keep the price of its crops competitive. Technological improvements like Eli Whitney’s cotton gin also helped increase cotton production and made slavery profitable.

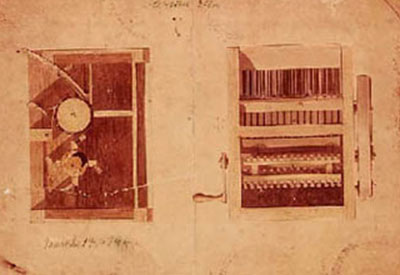

Cotton Gin

This is the drawing that Eli Whitney submitted to receive his patent for the cotton gin in 1794.

After the invention of the cotton gin, the yield of raw cotton doubled each decade after 1800. Demand was fueled by other cotton-related inventions of the Industrial Revolution, such as the machines to spin and weave it and the steamboat to transport it. By mid-century America was growing three-quarters of the worlds supply of cotton, most of it shipped to England or New England where it was manufactured into cloth. During this time tobacco fell in value, rice exports stayed steady at best, and sugar began to thrive, but only in Louisiana. At mid-century the South provided three-fifths of Americas exports--most of it in cotton.

However, like many inventors, Whitney (who died in 1825) could not have foreseen the ways his invention would change society for the worse. The most significant of these was the growth of slavery. While it was true that the cotton gin reduced the labor needed to remove seeds, it did not reduce the demand for slaves to grow and pick the cotton. In fact, the opposite occurred. Cotton growing became so profitable for the planters that it greatly increased their requirements for both land and slave labor.

Questions

What other agricultural inventions have had unintended positive and negative consequences in American history? Why?

Eli Whitneys Patent for the Cotton Gin, National Archives [online].

Southern Dependency

Although the South experienced prosperity for many years because of its cotton and tobacco plantations, it depended on the northern states for many of life's necessities. Henry Grady, editor of an Atlanta, Georgia newspaper, gave his account of a funeral he attended.

The grave was dug through solid marble, but the marble headstone came from Vermont. It was a pine wilderness but the pine coffin came from Cincinnati. An iron mountain overshadowed it but the coffin nails and screws and the shovel came from Pittsburgh. . . . A hickory grove grew nearby, but the pick and shovel handles came form New York. . . . That country, so rich in underdeveloped resources, furnished nothing for the funeral except the corpse and the hole in the ground.

Questions

How did this economic dependency contribute to the Civil War?

What part did this dependency play in ending the Civil War?

J. Jacobs, Cities and the Wealth of Nations (New York: Random House, 1984).

Slavery a Catalyst for Economic Power?

With the institution of slavery many Southern plantation owners had an economic advantage to inexpensively grow rice, sugar, tobacco, and later cotton. Listen to this Public Radio podcast interview of author Edward E. Baptist, historical scholar, on his book titled "The Half Has Never Been Told’ and respond to the following questions.

Questions

Would the U.S. have become a leading economic power without slavery?

How did the practice of slavery impact the growth of the United States?

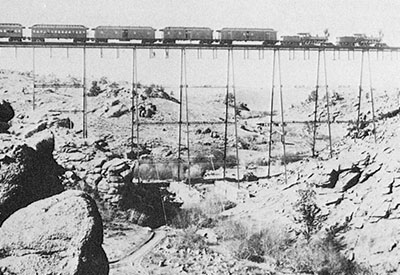

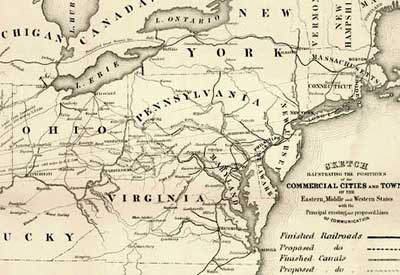

U.S. Transportation

This map of the United States, published about 1850, outlines all the major canals, railroads, and principal stage routes in the country.

Questions

What impact did these transportation systems have on the growth of the United States?

How could farmers and ranchers benefit from these transportation systems?

How did new transportation routes to the West affect the settlement of new American territories?

Why were there fewer transportation systems in the southern United States?

What did this difference mean for southern agriculture?

How have improvements in modern transportation affected agriculture today?

The Public Land Act authorized federal land sales to the public in minimum 640-acre plots at $2 per acre in an attempt to encourage the settlement of western lands. Unfortunately, the majority of those who purchased these lands tended to be speculators, rather than settlers.

Western Lands and Territories

Until 1776, the much of the land west of the Mississippi River was owned by Spain. The Public Land Act opened uncontested "western lands and territories" to those who would settle and expand the United States in these outlying areas. To learn more about the Public Land Act and the influence of subsequent land acts including what is meant by "squatters rights" (a term you may have heard) “cabin rights,” “corn rights,” or “tommyhawk rights,” read a brief post from World History on The Later Land Acts, 1796-1862.

Questions

As a settler, what would you be looking for in terms of land and resources necessary to survive?

New technologies on the farm and in transportation result in growing agricultural exports. The railroad era begins with Peter Cooper's railroad steam engine, the Tom Thumb, running 13 miles in 1830. By 1860, nearly 30,000 miles of railroad had been constructed.

Exports 1800-1850s

From 1800-1809, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $23 million or 75% of total exports.

From 1810-1819, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $40 million/year or 87% of total exports.

From 1820-1829, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $42 million/year or 65% of total exports.

From 1830-1839, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $74 million/year or 73% of total exports.

From 1840-1849, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $90 million/year or 65% of total exports.

From 1850-1859, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $189 million/year or 81% of total exports.

Questions

What historical event(s) or underlying factors can be used to make sense of the data?

Why is this data relevant?

What is one important idea you have learned from this information?

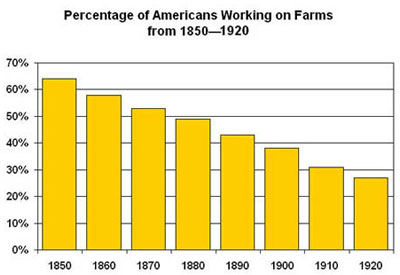

Farm Labor Comparisons

In 1830, about 250-300 labor-hours were required to produce 100 bushels (5 acres) of wheat with a walking plow, brush harrow, hand broadcast of seed (scattering of seeds by hand), sickle, and flail.

In 1850, it took about 75-90 labor-hours to produce 100 bushels (2 1/2 acres) of corn with a walking plow, harrow, and hand planting.

In 1840, the average total U.S. population was 17,069,453, and farmers made up 69% of the labor force.

In the 1850s, the U.S. population was 23,191,786, and farmers made up 64% of the labor force. During this time there were 1,449,000 farms and the average farm size was 203 acres. It took about 75-90 labor-hours required to produce 100 bushels (2 ½ acres) of corn with walking plow, harrow, and hand planting.

As the U.S. population grows the farm population shrinks. How do fewer farmers continue to feed a growing population?

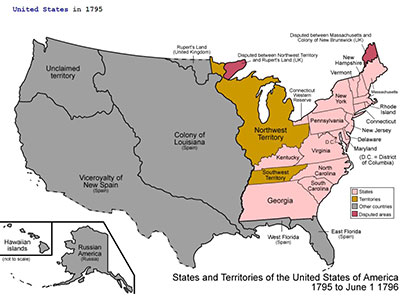

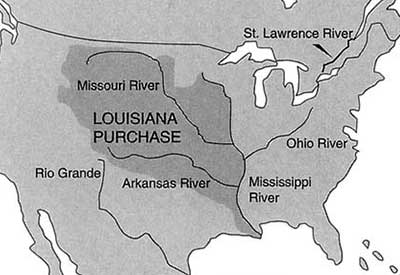

President Thomas Jefferson acquired the Louisiana Territory by purchasing it from France in 1803 for $15 million dollars, an average of four cents per acre. With this purchase, the geographical size of the United States doubled and opened the west for expansion.

Doubling the Size of the United States

President Thomas Jefferson acquired the Louisiana Territory by purchasing it from France in 1803. With this purchase, the geographical size of the United States doubled.

Questions

Why would this large addition to the territory of the United States excite farmers, ranchers, and immigrants?

How do you think the Indian tribes living in this region may have felt about their land being owned by the United States? Why?

What challenges did families who wanted to establish farms or ranches in this new territory face?

What challenges would the acquisition of such a large area of land pose to a young democratic government?

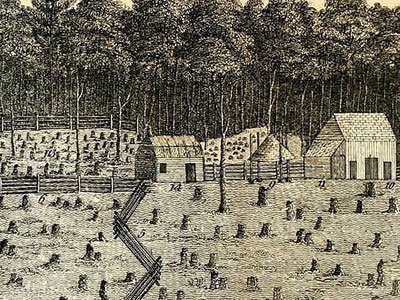

A plantation was a landholding large enough to be distinguished from the family farm, generally over 250 acres with a distinct division of labor (slaves) and management, with the latter primarily handled by the owner but often administered through an overseer. On a plantation you would find specialized production, usually with one or two cash crops. In contrast, Southern farms were smaller parcels of land that were generally run at the subsistence level by families. Farmers grew a greater variety of crops than did most planters, and they consumed much of their harvests themselves. They also depended on smaller labor forces--generally family members and in some cases a few slaves. In contrast to a plantation, a farm was typically administered by the owner without an overseer, thereby blurring the delineation between management and physical labor.

Prunty, M. (1955). The renaissance of the southern plantation. Geographical Review, 45(4), 459-491.

Differences Between Plantations and Farms

Great planters with very large holdings were a small minority among landowners. In 1860, only 2,300 planters (about five percent) owned 100 or more slaves. Thus the landscapes that they created were the exception rather than the rule in the antebellum South. Statistically, a significant percentage of slaves lived and worked on large plantations. Slaves living on plantations developed strong family alliances and ultimately forge a distinct culture. Use Wikipedia to see what others say about the differences between a farm and plantation and answer the following questions.

Questions

What were the differences between plantations and farms?

What is different about the number of types of crops grown on each? Why?

Why were black family groups more stable on large plantations than on small farms?

What percentage of southern farmers owned plantations?

Plantation Agriculture

Plantation economies were profitable in the south because of longer growing seasons (almost year-round), fertile soil, and many waterways in the area that made transportation much easier. The economy of the South was based on maximizing yields on large plantations. There were hand tools and implements pulled by horses but no machines so to get crops planted and harvested required many laborers. Although the majority of white southerners did work their own farms, large plantation owners used slave labor to plant and harvest cash crops, such as rice, tobacco, cotton, sugarcane, and indigo. Cash crops were commodities that were grown in large quantities and provided wide profit margins to the plantation owner. Profit, being the overall goal, required the use of cheap labor, and slavery kept the costs down. Using both slave men and women doing grueling work for eighteen hours a day, owners were able to create a labor force with little cost, since successive generations born on the plantations would automatically increase the number of laborers. Depending on location and the market plantation owners grew rice, sugar, tobacco, and later cotton.

The early English and European colonists had no experience in cultivating rice; however, examples of rice cultivation were available from African slaves, who did have knowledge on the subject. Construction of rice fields was a daunting task. Dirt walls, or banks, had to be created to keep out salt water, while ditches and gate were built to move fresh water in. In places like Delaware, 30,000 acres of swampland needed to be cleared before even attempting to construct rice fields. Rice seedlings were spread over and trampled into the soil by the feet of female slaves. The rice fields had to be flooded and drained, after which slaves acted as scarecrows to shoo away the birds. The rice was flailed (beaten), the hulls were removed, and the rice was polished before exporting. Rice was the major cash crop in Georgia and South Carolina by the 1690s. Rice gained popularity and quickly spread to other southern colonies, becoming one of the top ten exports during Colonial America.

Sugarcane, a tall, tropical grass, was first imported to the US from the West Indies; then grown in the south after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Best grown on rich flat land, sugarcane grows from 4 to 12 feet tall with a diameter up to 2 inches. Construction of sugarcane fields required 12-inch rows with seeds planted by hand at 36-inch intervals. When harvesting, the cane is cut toward the bottom of the stalk, leaving a portion to regrow for up to four times before having to be replanted. Slaves on sugar plantations, including women, men, and children, were responsible for planting 5,000-8,000 seeds that would produce one acre of sugarcane. Not only was sugar essential to England for tea, sugarcane was used to produce molasses, a major ingredient in rum, which was a key part of the Triangular Trade.

By the early 1790s, the use of slaves began to decline. Because Europeans could purchase rice and tobacco more cheaply from other British colonies, they refused to pay higher prices from the American colonies. In addition, cotton growers were struggling with making a profit because of the difficulty and time-consuming method of removing the seeds from the fiber. However, Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1794 changed the economy of the South. With the use of a cotton gin, a single laborer could clean the amount of cotton bolls as 50 slaves working by hand. By 1860, cotton sales earned more money than all other US exports combined. Cotton had become king.

Questions

How important were sugar, rice, and cotton to the southern United States?

What kind of labor was required to farm these crops?

How would the abolition of slavery after the Civil War affect the production of these crops in the South?

What are some of the major crops grown in your state today?

How much labor is required to produce these crops, and who provides the labor?

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database from Emory University

Many of the leaders of the American Revolution, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, were farmers. Both Washington and Jefferson were interested in experimenting with agriculture.

The First Mule Breeder

At his Mount Vernon, Virginia farm, George Washington experimented with crop rotation and with new seeds and plants. He also became the Nations first mule breeder, using animals given to him by Charles III, the king of Spain in 1785. Of two donkeys sent across the Atlantic, "Royal Gift" was the only donkey to survive. Being better draft animals than horses and requiring less food, mules are a cross between a male donkey and a female horse. Washington believed that mules would revolutionize farming.

To learn more about different types of animals on Washington's farm, use the link below.

The Animals on George Washington's Farm

Questions

Why is Washington called "The Father of the American Mule"?

Other than mules, what types of animals were found on George Washington's farm?

Which animals do you think were most significant in helping Mount Vernon become a successful farm?

Bakmas, Johanna. "Royal Gift (Donkey)." Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. 2018. Web. 27 July 2018.

George Washington

George Washington served America in many roles, including first U.S. President, Commander in Chief of the Revolutionary Army, and farmer. Visit the Mount Vernon website to read about George Washingtons contributions to agriculture.

See Washington's contributions

Questions

Why do you think George Washington was so passionate about the land?

Does it surprise you that the President of the United States was a farmer? Why or why not?

Thomas Jefferson's Experiments

Thomas Jefferson also enjoyed experimenting with agriculture on his Virginia estate at Monticello. Both Washington and Jefferson helped organize societies for improving agriculture.

Jefferson grew 330 varieties of vegetables in his 1,000-foot-long garden terrace at Monticello, along with 170 fruit varieties. The south-facing terrace garden created a micro-climate, in which summer heat was capture and the cold winter was tempered.

Jefferson obtained new vegetable varieties from foreign dignitaries, and handed out vegetable seeds from these plants to his friends, family, and fellow politicians. Highly valuing diverse plants, he equated the introduction of an olive tree and upland rice into the United States to his writing of the Declaration of Independence.

During his service as an ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson recognized that European plows were insufficient. In 1788, he redesigned the moldboard of the plow, the part that lifts up and turns over the soil. Monticello plows were used as early as 1794. Originally made of wood, Jefferson had the moldboard replaced with iron in 1814.

As president, Jefferson promoted the idea of commercial market gardening. He kept records of the introduction of thirty-seven vegetables at Washington, DC market gardens, and gave gardeners samples of new vegetables he obtained. In addition, Jefferson advocated the use of manure to remedy deficits in the soil, which is widely used today.

Questions

What was the significance of the Monticello plow?

Why do you think Jefferson is referred to as an innovator, rather than an inventor?

Regarding agriculture, what is Jefferson's greatest legacy?

Hatch, Peter. "Thomas Jefferson's Legacy in Gardening and Food." Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. 2010. Web. 27 July 2018.

Useful Plants

Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States said, "The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture."

Questions

Why do you think Thomas Jefferson made such a bold statement?

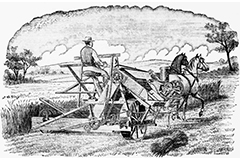

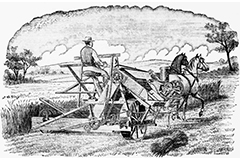

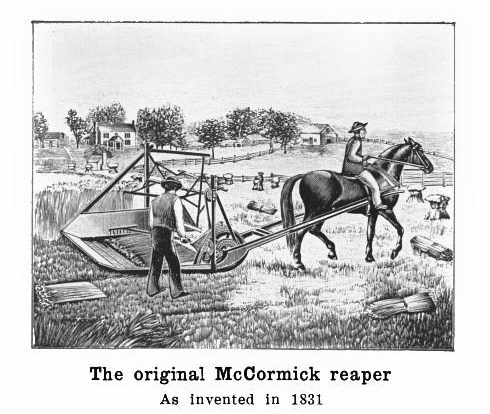

Farmers began to use horsepower to pull newly invented farm implements like the broadcast seeder and the mechanized grain reaper. These implements improved working conditions for farmers and provided more cash so that they could enjoy a better standard of living.

Horse-drawn Reaper

Cyrus McCormick, sometimes referred to as the Father of Modern Agriculture, made one of the most significant contributions to the success of U.S. agriculture by inventing the horse-drawn reaper in 1831. Read McCormick's biography on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology website to learn more about this remarkable man and his invention.

Questions

Why is Cyrus McCormick called the Father of Modern Agriculture?

Why was his invention so important to the success of U.S. agriculture?

Horsepower - A Unit of Power

One horsepower was originally defined as the amount of power required to lift 33,000 pounds one foot in one minute, or 550 foot-pounds per second or 745.7 watts. The term was adopted in the late 18th century by Scottish engineer James Watt to compare the output of steam engines with the power of draft horses. Watt (born in 1736) established the value for horsepower after he determined the strength of the average horse.

Questions

In what other contexts have you heard the term horsepower?

Besides agriculture, what have horses been used for?

By the 1800s the Northern states began to industrialize and export manufactured goods. With room to grow and resources to spare the United States government invested in exploration, opening new territories to farmers and ranchers. Technology was employed to develop transportation systems that brought produce and people together in a national market system. As the Northern states industrialized they attracted new immigrants, while the South's population stagnated. In 1800 half of all Americans lived in the South, but by 1850 only one-third of the population was there.

The Southern economy relied on producing and exporting cotton, sugar, rice, tobacco and wheat. The South also depended heavily on food imported from the upper-Mississippi valley. Production of work-intensive cash crops like cotton and tobacco expanded and the Southern economy became increasingly dependent on slave labor to keep the price of its crops competitive. Technological improvements like Eli Whitney's cotton gin also helped increase cotton production. This more efficient method for "ginning" or removing seeds from the cotton bolls with a machine, not by hand (which was done by slaves), lowered the cost of the processing cotton into thread. However, this innovation did not reduce the need for slaves, rather plantation owners increased their number of slaves to grow more cotton.

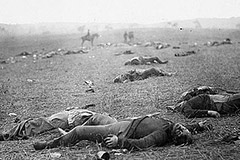

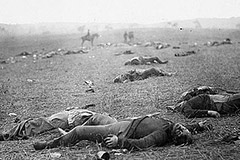

The slave-dependent Southern agricultural system worked only for a time. From 1861 to 1865, Americans fought a chaotic Civil War. For the South the war was a struggle to preserve their economy and way of life; for the North it was a struggle to preserve the Union and end slavery. Before the war sixty percent of Americans farmed, but when the war began large numbers of farmers left to fight so their land went untended. When peace was finally declared, many of the South's farms lay in ruin.

From 1850-1870, the US experienced its first agricultural revolution. The development of improved and more efficient farm technologies, as well as the increase of railroad networks, led to domestic and foreign demand of goods.

Exports 1860-1920s

From 1860-1869, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $182 million/year or 75% of total exports.

From 1870-1879, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $453 million/year or 79% of total exports.

From 1880-1889, the average annual value of agricutural exports totaled $574 million/year or 76% of total exports.

From 1890-1899, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $703 million/year or 71% of total exports.

From 1900-1909, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $917 million/year or 58% of total exports.

From 1910-1919, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $1.9 billion/year or 45% of total exports.

From 1920-1929, the average annual value of agricultural exports totaled $1.94 billion/year or 42% of total exports.

Questions

How could you explain the drop in agricultural exports from 1860-1869? Why is this relevant?

How does the data reflect the economy of the nation?

In the 1860s the average total U.S. population: 31,443,321; farm population: 15,141,000 (est.); farmers 58% of labor force; Number of farms: 2,044,000; average acres: 199.

In the 1870s the average total U.S. population: 38,558,371; farm population: 18,373,000 (est.); farmers 53% of labor force; Number of farms: 2,660,000; average acres: 153

In the 1880s the average total U.S. population: 50,155,783; farm population: 22,981,000 (est.); farmers 49% of labor force; Number of farms: 4,009,000; average acres: 134

In the 1890s the average total U.S.population: 62,941,714; farm population: 29,414,000 (est.); farmers 43% of labor force; Number of farms: 4,565,000; average acres: 136. During this time it took 40-50 labor-hours to produce 100 bushels of wheat on 5 acres using a gang plow, seeder, harrow, binder, thresher, wagons, and horses; 35-40 labor-hours required to produce 100 bushels (2 1/2 acres) of corn with 2-bottom gang plow, disk and peg-tooth harrow, and 2-row planter.

In the 1900s the average total U.S. population: 75,994,266; farm population: 29,414,000 (est.); farmers 38% of labor force; Number of farms: 5,740,000; average acres: 147

In the 1910s the average total U.S. population: 91,972,266; farm population: 32,077,000 (est.); farmers 31% of labor force; Number of farms: 6,366,000; average acres: 138

In the 1920s the average total U.S. population: 105,710,620; farm population: 31,614,269p; farmers 27% of labor force; Number of farms: 6,454,000; average acres: 148

As the U.S. population grows the farm population shrinks. How do fewer farmers continue to feed a growing population?

Northern farmers produced a variety of crops and livestock, sometimes supplemented by craftwork. Southern plantation agriculture concentrated on export crops. For the South the war was a struggle to preserve their economy and way of life; for the North it was a struggle to preserve the Union, grow the economies of one nation, and end slavery. Before the war sixty percent of Americans farmed, but when the war began large numbers of farmers left to fight so their land went untended. When peace was finally declared, many of the South’s farms lay in ruin.

Labor Force

In 1860, farmers made up 58 percent of the labor force. It is estimated that during the Civil War over a million farmers left their fields to serve as soldiers.

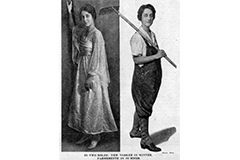

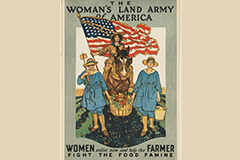

During the Civil War, women took on the role of men in farming, running plantations, and spying. Some women even dressed up as men and served in the military.

For additional information about industry and economy during the Civil War, read the following:

Industry and Economy During the Civil War

Questions

What did the North and South do to make up for this critical loss of farm labor?

How would the loss of men working on farms and ranches have affected American society?

History of American Agriculture, 16072000, U.S. Department of Agriculture [online].

The Divide Between North and South

The Civil War began with the firing on Fort Sumter, South Carolina in 1861, and ended in Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia in 1865. Use the link below to learn more about the two distinct regions during this time period.

Questions

Compare and contrast agriculture in the North and the South. Discuss similarities and differences.

Who had the economic advantage during the Civil War? Explain.

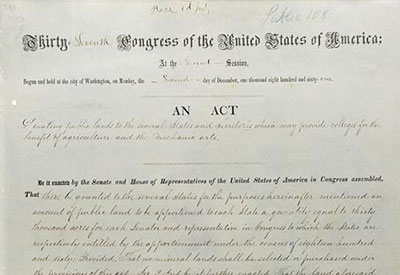

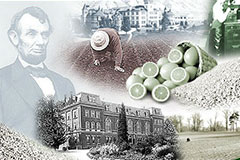

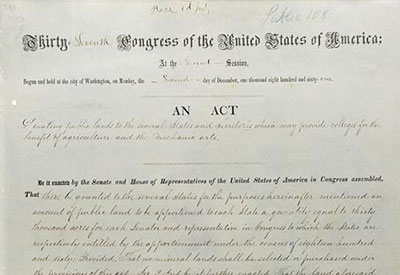

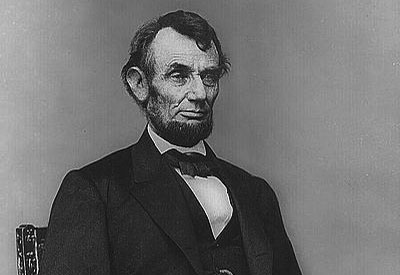

In 1862, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln created the United States Department of Agriculture, or USDA. The "people's department", as Lincoln called it, was created to "acquire and to diffuse among the people of the United States useful information on subjects connected to agriculture." That year the Morrill Act also gave each state thirty thousand acres of public land per seat held in Congress to help build and maintain agricultural colleges. The Hatch Act of 1887 granted additional lands and funds to universities for agricultural research and experimentation. In 1890, a second Morrill Act funded black agricultural colleges.

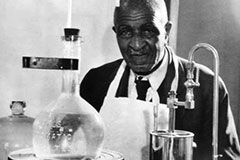

Government support of science, technology, and education to improve agriculture gave American farmers an edge over the rest of the world. Research into new varieties of foodstuffs (such as navel oranges for California and sugar beets for the Midwest), the introduction of early organic insecticides, and fertilizer testing programs were a few of the early USDA projects undertaken to improve agriculture and life in America. As the USDA shared its discoveries with the American public the landscape began to change. Farmers returning to their crops and livestock from agricultural science schools and agricultural demonstration and extension programs began experimenting with new technologies to improve production.

The Homestead Act offered 160 acres of free land to settlers who would farm it for five years, making the Great Plains a land of opportunity. Homesteaders rushed to fill the open lands. Homesteading also brought fresh waves of immigrants in pursuit of their dreams. In 1870 nearly half of all Americans worked as agricultural laborers and more than three-fourths of America’s exports were agricultural goods. Westward expansion pushed the agricultural frontier further into the Great Plains. The Great Plains states (Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming) with rich soil yielding bountiful harvests of wheat and corn would become America’s breadbasket,

The Homestead Act

Visit the Homestead National Monument of America website to learn more about the Homestead Act of 1862.

Visit the Homestead National Monument website

Questions

Why has the Homestead Act of 1862 been called one the most important pieces of legislation in the history of the United States?

If you had been around in the1860s, would you have tried to claim a homestead? Why or why not?

Sod Houses

Farmer homesteaders in the Great Plains were sometimes called sodbusters. These hardy pioneers, often new immigrants, dealt with inadequate housing, water, and fuel as well as extreme environmental conditions. Characteristically persevering people, they made the land productive and built houses, called soddies, from the earth. The sod house reflects the never-say-die attitude of these farmers.

Questions

Why would people want to homestead knowing that they would face such harsh living conditions in a sod house?

Are there people living in similar circumstances today?

The Plight of American Natives

The way of life for Native Americans living on the plains was destroyed by the slaughter of the buffalo, which were almost exterminated by indiscriminate hunting in the decade after 1870. Read this excerpt from the U.S. State Departments Outline of American History:

Government policy ever since the Monroe administration had been to move the Indians beyond the reach of the white frontier. But inevitably the reservations had become smaller and more crowded, and many began to protest the governments treatment of Native Americans. Helen Hunt Jackson, for example, an Easterner living in the West, wrote a book, A Century of Dishonor (1881), which dramatized the Indians plight and struck a chord in the nations conscience. Most reformers believed the Indian should be assimilated into the dominant culture. The federal government even set up a school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in an attempt to impose white values and beliefs on Indian youths. (It was at this school that Native American Jim Thorpe, often considered the best athlete the U.S. has produced, gained fame in the early 20th century.)

In 1887 the Dawes Act reversed U.S. Native American policy, permitting the president to divide up tribal land and parcel out 65 hectares of land to each head of a family. Such allotments were to be held in trust by the government for 25 years, after which time the owner won full title and citizenship. Lands not thus distributed, however, were offered for sale to settlers. This policy, however well-intentioned, proved disastrous, since it allowed more plundering of Indian lands. Moreover, its assault on the communal organization of tribes caused further disruption of traditional culture. In 1934 U.S. policy was reversed again by the Indian Reorganization Act, which attempted to protect tribal and communal life on the reservations.

Questions

How and why did the U.S. government policy toward the Native Americans change at the end of the1800s?

What other options could the government have pursued in dealing with Native American tribes?

What impact did the policy of removing Native Americans from their tribal lands have on agricultural expansion in the United States?

Howard Cincotta, ed., Plight of the Indians, An Outline of American History, U.S. Department of State, Bureau of International Information Programs [online].

Barbed Wire

When pioneers began settling their new homesteads across the Great Plains, they found few trees or other fence-building materials to secure their livestock. Settlers initially built fences from thin, smooth wire, but soon learned that the smooth wire would not prevent their animals from wandering off.

Then, in 1868, Michael Kelly invented the first improved wire fencing--barbed wire. In 1874, Joseph Glidden improved upon Kellys design, and by the mid-1870s the widespread use of barbed wire had greatly changed life in the western United States.

Author Robert Clifton wrote the following:

The invention of barbed wire probably had as much influence on the settlement of the American West as the revolver and the repeating rifle. It certainly had a greater civilizing effect, for the progress of the taming of the frontier is reflected in the increasing number and diversification of barbed wire patents in the final decades of the last century.

Use the information provided above, and the additional links provided below to answer the questions:

The impact of barbed wire on the Great Plains website

Questions

Why did Clifton say that barbed wire had as much influence on the settlement of the American West as the revolver and the repeating rifle?

How was barbed wire helpful in the establishment of homesteads across the Great Plains?

What challenges did barbed wire create for homesteaders?

What other inventions made a dramatic impact on the settlement of the West?

Robert Clifton, Barbs, Prongs, Points, Prickers and Stickers: A Complete and Illustrated Catalogue of Antique Barbed Wire (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998).

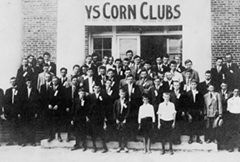

The Morrill Act gave each state thirty thousand acres of public land per seat held in Congress, to help build and maintain agricultural colleges. The Hatch Act of 1887 granted additional lands and funds to universities for agricultural research and experimentation. In 1890, a second Morrill Act funded black agricultural colleges.

Land-Grant Institutions

The three cornerstones of the land-grant approach--teaching, research, and extension--have improved the economic well-being and quality of life of all Americans. The first Morrill Act, passed in 1862, established land-grant institutions so that the average citizen could obtain an education. These colleges offered courses in agriculture and mechanical arts in addition to classical studies. Learn the what, why, where, who, when, and how of land-grant colleges by following the link below.

Visit the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities Website

Questions

What is the purpose of land-grant institutions?

What does this tell you about the priority of research and education in the U.S. government?

How has the tradition of land-grant universities affected you and your family?

Government support of science, technology, and education to improve agriculture gave American farmers an edge over the rest of the world. Research into new varieties of foodstuffs (such as navel oranges for California and sugar beets for the Midwest), the introduction of early organic insecticides, and fertilizer testing programs were a few of the early USDA projects undertaken to improve agriculture and life in America.

Disseminating Research

The USDA issued its first research bulletin in 1862. This first issue presented new research findings about the sugar content of several grape varieties and the suitability of each for wine making.

Questions

What is the purpose of keeping others up to date on current research?

Is it possible that the research was already out of date by the time the bulletin was published?

What means do we have for communicating research findings today?

ARS Timeline: 138 Years of Ag Research, U.S. Department of Agriculture [online].

In 1862, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln created the United States Department of Agriculture, or USDA. The “people’s department”, as Lincoln called it, was created to “acquire and to diffuse among the people of the United States useful information on subjects connected to agriculture.”

Abraham Lincoln and Agriculture

On May 15, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed an act of Congress into law establishing at the seat of Government of the United States a Department of Agriculture. Read this brief history, entitled Abraham Lincoln and Agriculture, at the National Agriculture Library website.

Visit the National Agriculture Library website

Questions

What aspects of Lincoln's life made him enthusiastic about agriculture?

What did he do as President to make sure that agriculture was successful in America?

Commissioner of Agriculture

Before the Department of Agriculture became a Cabinet-level agency in 1889, the head of the USDA was called the Commissioner of Agriculture. In 1862, President Lincoln appointed Isaac Newton the first Commissioner. The act creating the USDA directed the Commissioner to:

“acquire and preserve in his Department all information concerning agriculture which he can obtain by means of books and correspondence, and by practical and scientific experiments (accurate records of which experiments shall be kept in his office), by the collection of statistics, and by any other appropriate means within his power to collect, as he may be able, new and valuable seeds and plants to test, by cultivation, the value of such of them as may require such tests to propagate such as may be worthy of propagation, and to distribute them among agriculturists.”

Questions

How is the Secretary of Agriculture selected today? To whom does he/she report?

Why is this position so important?

G. Baker, J. Porter, W. Rasmussen, and V. Wiser, eds., Century of Service: The First 100 Years of the United States Department of Agriculture (Washington, D.C.: Centennial Committee, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1963).

The Civil War destroyed much of the South and its plantations. More dramatically, four million slaves were suddenly freed with no land, no money and little opportunity. A tenant farming system called sharecropping evolved in the South to make use of cheap labor. Sharecropping employed ex-slaves and other poor workers to farm the cotton and tobacco fields of landowners in exchange for part of the harvest. This system persisted for decades, even though sharecroppers were frequently cheated and exploited.

Post-war Agriculture in the South

The following account describes life in postwar Georgia.

The southern states were devastated by the Civil War. Georgia, for example, lost sixty-six percent of its developed resources during the war. Post-war farming practices in the south were in the midst of monumental changes as former slaves were emancipated. Prior to the war there were more than a thousand plantations in Georgia that were at least one thousand acres in size, but after the war farm size was based on the area a man could manage through his own labor, with the assistance of his family or contracted labor. In addition:

The plantations (farms) of the country were in a rough and dilapidated condition generally: stock, mules and horses for plow-teams were scarce, as was also grain to feed them . . . most of the seed was old and imperfect from neglect during the war . . . and the laborers generally disinclined to do full work.

Questions

How did the emancipation of slaves change farm life in the southern states?

How did it change life in the rest of the United States?

P. B. Haney, W. J. Lewis, and W.R. Lambert. Cotton Production and the Boll Weevil in Georgia: History, Cost of Control, and Benefits of Eradication, Georgia Agricultural Experiment Stations, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University o

Plowing with Mules

Until the invention of tractors, horses and mules were the primary source of power for farmers to do their work on the farm and ranch. Examine the image above of a farmer plowing his field. A team of two horses or mules pulling a walking plow could work only about two acres per day. This limited the practical size of the farm for one farmer to about one hundred acres. In contrast, when early steam tractors became available after 1868, they could plow an acre in just half an hour.

Questions

How many acres could a farmer plow in a twelve-hour day with a steam plow?

What impact do you think changing from horse to machine power had on the average size of farms in America?

What factors may have kept some farmers from modernizing to steam- and later gas-powered tractors?

What factors today keep people from adopting new technologies for work?

What factors encourage them to adopt new technologies?

Farming in the 1920s: Machines, Wessels Living History Farm, York, Nebraska [online]; and Franklin Harris and George Stewart, The Principles of Agronomy (New York: Macmillan, 1930).

Sharecropping

Sharecropping is often thought of as an activity that involved only poor African American farmers. However, many sharecroppers were poor white farmers. Below is an excerpt from “Better a Tent than a Mortgage,” the oral history of a poor white farmer named Walter Strother, collected by writer L. E. Cogburn as part of the Federal Writers’ Project (1936–1940). This government project provided work for many writers during the Great Depression.

“I was born on the Wateree River fifty years ago, and lived there until I was six years old. My father then moved to Derrick’s Pond, about seventeen miles southeast of Columbia, [South Carolina]. The next year, when I was just seven years old, my father left us. I am the oldest of his family of seven children.

“In order to help my mother support our family, I had to plow in the fields at the age of eight years. I became a regular plowhand by the time I was ten. Mr. [Kerningham?], on whose place we lived, hired me by the day, at a wage of forty cents a day. We earned so little that my mother could afford to buy only the bare necessities. There were days that we had to go hungry. I, in the meantime, had received but a few months of schooling. I didn’t have time to go to school. I had to work.

“When I was twelve years old, and my brothers were large enough to help I asked Mr. Kerningham to let us work a sharecrop. I felt that this would afford us more to eat, because of an advance on a sharecrop.

“I’ll never forget the morning I went to Mr. Kerningham and asked him for a sharecrop. He was fixing to go to Columbia. Already had his horse hitched to the buggy. He said to me, ‘Son, you can’t manage a farm.’ I looked at him square in the face and said, ‘Give me a chance.’ He told me he would think it over, and for me to come back in a few days. I didn’t wait. I went back the next day, and he said, ‘Walter, I have decided to do it. When do you want to move?’ ‘Right away,’ I told him. ‘Go and catch Kit and Beck and hitch them to the wagon and move,’ he told me.

“That year, I made seven bales of cotton and plenty of corn, peas, and potatoes. And we didn’t have to go hungry at any time.

“Mr. Kerningham used the lien system to run his farm. He traded with M. E. C. Shull, who ran a big grocery store in Columbia on Main Street, between Taylor and Blanding.

“That fall, after we started to pick cotton, I went to Mr. Kerningham and said, ‘I have a bale of cotton out.’

“’You know you haven’t a bale already,’ he replied.

“’Yes, I have, too.’

“’When do you want to gin it? It’s bringing a little more than eight cents now.’

“’I’ll do as you say. You know best.’

“’Suppose you gin it tomorrow,’ he said.

“He had a gin on the place, and the next day I had it ginned. I went to Mr. Kerningham and said, ‘I want you to sell it for me.’

“’No, you take the wagon and haul it to Columbia and sell. I’ll meet you at the store.’

“I tied my mules to the hitching post on Assembly Street. I remembered how my father did when he sold cotton. I cut the side of each bale and pulled a sample and took it to the buyer and asked him what he would bid on it. Taking the samples and examining them he said, ‘I’ll give you eight cents. Might give you more after I see the bales. Where are they?’ We went to the wagon, and he pulled a sample from each bale. After examining it, he said: ‘I’ll give you eight and a half, if you’ll sell it now and not try to get a higher bidder.’

“I sold it to him and took the check to the store and met Mr. Kerningham. He said to me, ‘Have you sold your cotton?’

“’Yes, sir,’ I replied. And at the same time I handed him the check.

“’What did you get for it?’ he asked.

“’Eight and a half cents a pound.’

“’That’s good.’

“We walked to the back end of the store. He sat down on a bag of oats, and I sat on,--I don’t remember what. I didn’t know much ‘rithmetic, but I had already counted up what was to come to me. He was dividing it up, after taking off the cost of bagging and ties and ginning. He said to me, ‘You have so-and-so for your part. How much do you want?’

“’Not a dime.’

“’You don’t want any at all?’

“’No, sir. Put it to my credit on my account,’ I told him.

“I furnished the labor and paid for half the fertilizer, and he furnished and fed the stock and paid for half the fertilizer. We divided everything that was made half-and-half, except the potatoes. I had all of these that I made.

“I worked this way two years with Mr. Kerningham. Saw that he was getting the best of it, as I thought then. But there wasn’t the slightest misunderstanding between us.

“The next year, I moved away from him and rented. I bought a plug mule and got one of those liens. Had a bad crop year, and didn’t make enough to pay the rent and lien. I took the mule back to the man I bought it from. He didn’t have to come for it. I explained to him that I had nothing to pay, and he was mighty nice about it. Took the mule back and didn’t blame me.

“I sold everything to settle up and was left flat again, like the first time I went to the old man.

“I found out that I made a mistake when I left Mr. Kerningham. I went back and asked him for a crop again, and he gave it to me. I was a pretty big boy then, whole lot of difference from the first time.

“This year I made a good crop, got a fair price for it, and cleared a little money.”

Questions

What is the farmer’s attitude about sharecropping?

What lessons, if any, can be learned from the way Walter Strother faced the challenges of his life as a sharecropper?

L. E. Cogburn, Better a Tent Than a Mortgage, American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers Project, 19361940, Library of Congress, American Memory [online].

Reconstruction

The period of rebuilding in the South after the Civil War was called “Reconstruction.” Here is an account of Reconstruction from a publication by the National Park Service.

“Although the exact dates demarcating Reconstruction are not universally agreed upon, Eric Foner indicates the years 1863 to 1877: the period from the Emancipation Proclamation to the year that the ideal of Reconstruction to protect the fundamental rights of all citizens gave way to southern ‘Redemption’ and ‘home rule,’ the equivalent to white rule. (Still others might point to 1883 as the end of Reconstruction, the year the Supreme Court declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional.) By law, at least, African Americans made significant gains for their rights as citizens during Reconstruction. Racism prevailed however, and once ‘Southern Redemption’ took hold by the 1880s, racist policies continued and proliferated. Federal laws, Supreme Court decisions, and presidential initiatives would vacillate between furthering and hindering the civil rights of African Americans.

“Following the Civil War, Congress amended the Constitution in ways that confirmed American democracy and raised the hopes of African Americans for attaining equality. The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of 1865 and 1867 ended the institution of slavery and guaranteed equal protection under the law regardless of race, respectively. The adoption of restrictive ‘Black Codes’ by southern states however, sought to secure white supremacy and keep blacks as a laboring class. President Andrew Johnson’s moderate policy supported the concerns of the South and did little to advance blacks’ civil rights. Nonetheless, Congress passed bills to ensure civil rights and enforce Reconstruction in the South with the passage of a civil rights bill in 1866 and the Reconstruction Act of 1867 (i.e., ‘Radical Reconstruction’). Finally, the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1869 allowed black men to vote.

“The federal government did much to improve and aid the newly freed slaves through the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865. Among the many services provided, the Bureau supplied legal aid, set up schools, and provided health care. Also during Reconstruction, African-American men gained seats in Congress: two in the Senate and twenty in the House of Representatives. Despite the accomplishments, racism operated to subvert equality and justice.

“The economic depression of the 1870s was particularly severe in the South: yeomen farmers were engulfed by poverty and planters by indebtedness. Just as African Americans were increasing their political influence, the depression limited their power to influence working conditions: independent black farming became difficult so that most owners and renters were reduced to sharecroppers and wage laborers. Resentment and resistance among white southerners would increasingly undermine the law of the land through organized acts of violence and state legislation.

“Supreme Court decisions hastened the end of Reconstruction. Under the Enforcement Act of 1870, indictments were made against several southerners who were charged with preventing blacks from voting. In 1875, the Court’s decisions favored the defendants and interpreted the Fifteenth Amendment in an ambiguous fashion. By 1877, radical Republicanism gave way to conservative policies favoring southern Democrats and ‘home rule’ was restored to southern states. Finally, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was declared unconstitutional in 1883 and the constitutional laws that were supposed to guarantee African-American citizenship rights were successfully subverted.”

Questions

What were the goals of Reconstruction?

What obstacles did Reconstruction face?

How well were the goals of Reconstruction achieved?